Notable Recognition

3x Winning Founder and CEO

Technology Fast 50 | Technology Fast 500™

Deloitte

2025 Top 10 Thought Leader in Transformation

2025 Top 25 in Innovation and AI

2025 Top 50 in Leadership and Governance

Thinkers360

2× Thinkers50 Distinguished Achievement Awards

nominee (Strategy 2023 | Digital Thinking 2025)

Thinkers50

100 Most Influential People in Technology

Ziff-Davis Enterprise

3x Wall Street Journal Bestselling Author

REINVENT (#1), Everything Connects (#2), LIFT (#1)

3x USA Today Bestselling Author

TRANSCEND, Everything Connects, LIFT

Leaders to Watch

American Management Association

Bestselling Author of TRANSCEND

USA Today (#1 in Computers, #1 in Philosophy,

#3 in Business & Economics, #5 in All Non-Fiction, #12 in All Books)

#7 Los Angeles Times

#25 Publishers Weekly

#1 Amazon

#1 Barnes & Noble

A Financial Times Book of the Month

“Must Read” by the Next Big Idea Club

Mindvalley Book Club’s 4 Best New Releases

2025 Goody Business Book Awards

2025 American BookFest Awards

2025 Gold Winner of the Literary Titan Book Awards

2025 Pencraft Annual Book Awards

2025 Royal Dragonfly Book Awards, 1st Place, Science & Technology

Thinkers360 Top 50 books to read in 2026

DisrupTV’s Top 25 Books of 2025

2025 American Writing Awards

A double category winner in the 2025 Goody Business Book Awards

– BUSINESS – PROBLEM SOLVING

– LEADERSHIP – THINK DIFFERENTLY

Bestselling Co-Author of Reimagining Government

USA Today

Los Angeles Times

#1 Amazon New Release

Gold Winner of the Literary Titan Book Awards

Finalist of the 2025 American Writing Awards

Bestselling Author of REINVENT

#1 Wall Street Journal

#1 Amazon

#1 Barnes & Noble

2024 Axiom Business Book Awards

Gold Medalist in Business Disruption/Reinvention

2024 NABE Pinnacle Achievement Awards

Best Business Book

2024 Soundview Business Book of the Year Shortlist

2024 Book Excellence Award Winner in Business

2023 INDIES Book of the Year Finalist

Foreword Reviews | Business & Economics

2024 Independent Press Awards

Business Category

13th Annual 2023 Globee® Awards for Business

2023 Best Business Book | Silver Winner

Feathered Quill Book Awards

2024 Silver Award | Business/Informational Category

2023 Global EBook Awards

Best Business Book | Gold Winner

The 21st Annual American Business Awards®

2023 Best Business Book of The Year | Silver Stevie Winner

2023 American Book Fest Best Book Awards Winner

in the Business: Management & Leadership Category

Best Indie Book Award®

International Literary Award | 2023 BIBA® Non-Fiction: Business Winner

14th Annual Awards | American Books Fest

2023 International Book Awards

IBA Best Business Book in the Category of Business: Management and Leadership

PenCraft Seasonal Book Award

2023 Summer Best Book | Business/Finance

2023 Independent Author Network

Book of the Year Awards Finalist | Business/Sales/Finance

Bestselling Author of LIFT

#1 Wall Street Journal

#111 USA Today Combined List

#1 Amazon

#2 Barnes & Noble

2023 Readers Favorite Book Awards

Gold Medalist in Business/Finance

2023 Axiom Business Book Awards

Gold Medalist in Independent Thought Leaders

2023 Nautilus Book Award

Silver in Business and Leadership

2023 Book Excellence Award Winner in Leadership

PenCraft Seasonal Book Award

2023 Spring’s Best Book | Business/Finance

PenCraft Seasonal Book Award

2023 Winter’s Best Book | Business/Finance

14th Annual Awards | American Books Fest

2023 International Book Awards

IBA Finalist in the Category of Business: Management and Leadership

American Book Fest

2022 Best Business Management and Leadership Book

Globee Awards

2022 Publication of the Year | Best Business Book

Stevie International Business Awards

2022 Publication of the Year | Best Business Book

Best Indie Book Award®

International Literary Award | 2022 BIBA® Non-Fiction: Business Winner

2022 INDIES Book of the Year Finalist

Foreword Reviews | Business & Economics

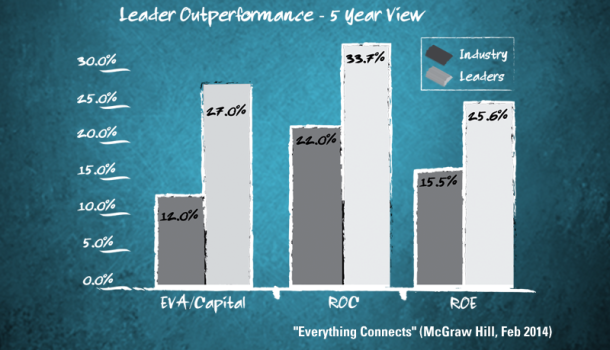

Bestselling Author of Everything Connects

#2 Wall Street Journal

#77 USA Today Combined List

#1 Amazon

#1 Barnes & Noble

Globee Awards

2023 Publication of the Year | Best Business Book

2023 Book Excellence Award Finalist in Business

2023 American Book Fest Best Book Awards Finalist

in the Business: Management & Leadership Category

2023 American Book Fest Best Book Awards Finalist

in the Business: Motivational Category

One of the 12 Business Books You Will Need to Read in 2014

Adam Grant, Wharton Professor, New York Times Bestselling Author of Give and Take

The Power of Convergence

One of the Best Business Books of 2011

800CEOREAD, CIO Insight

Winning the 3-Legged Race

Top 5 Transformation Books

CIO Insight

Sustained Innovation

Editor’s Picks: The 10 Best Business Books of 2007

CIO Insight